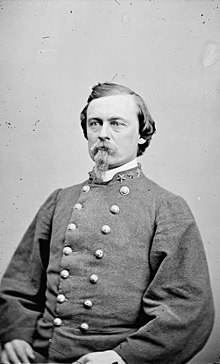

Joseph Finegan

Joseph Finegan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 17, 1814 Clones, County Monaghan, Ireland, U.K. |

| Died | October 29, 1885 (aged 71) Rutledge, Florida, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1862–65 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Florida Brigade |

| Battles / wars | American Civil War |

Joseph Finegan, sometimes Finnegan (November 17, 1814 – October 29, 1885), was an American businessman and brigadier general for the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. From 1862 to 1864 he commanded Confederate forces operating in Middle and East Florida, ultimately leading the Confederate victory at the Battle of Olustee, the state's only major battle. He subsequently led the Florida Brigade in the Army of Northern Virginia until near the end of the war.

Before the war, Finegan was a politician, attorney, lumber mill operator, slave owner, and railroad builder. He returned to business after the war, and worked as a cotton broker.

Early life and career

[edit]Finegan was born on 17 November 1814 at Clones, a small town in the west of County Monaghan in Ireland.[1] He came to Florida in the 1830s, first establishing a sawmill at Jacksonville and later a law practice at Fernandina. At the latter place, he became the business partner of David Levy Yulee and began construction of the Florida Railroad to speed transportation of goods and people from the new state's east coast to the Gulf of Mexico.[2]

Finegan's successes are perhaps attributable to his first marriage on July 28, 1842, to the widow Rebecca Smith Travers.[1] Her sister Mary Martha Smith was the wife of Florida's territorial governor Robert Raymond Reid, an appointee of President Martin Van Buren.[3]

At a courthouse auction in 1849, Finegan paid just twenty-five dollars ($25) for five miles of shoreline along Lake Monroe.[4]

In 1852, he was a member of the Committee of Vigilance and Safety of Jacksonville, Florida.[5]

By the outbreak of the American Civil War, Finegan had built his family a forty-room mansion in Fernandina, bounded by 11th and 12th Streets and Broome and Calhoun Avenues, the site of the modern Atlantic Elementary School. His family included his three stepdaughters Maria, Margaret, and Martha Travers;[6] and children Rutledge, Agnes, Josephine, and Yulee Finegan.[7]

At Florida's secession convention, Finegan represented Nassau County alongside James G. Cooper.[8]

Civil War

[edit]In April 1862, Finegan assumed command of Middle and East Florida from Brigadier General James H. Trapier.[9] Soon thereafter, he suffered some embarrassment surrounding the wreck of the blockade runner Kate at Mosquito Inlet (the modern Ponce de Leon Inlet). Her cargo of rifles, ammunition, medical supplies, blankets, and shoes was plundered by civilians. Attempts to recover these items took months before he issued a public appeal. Eventually, most of the rifles were found, but the other supplies were never recovered.[10] Also in 1862, recognizing the importance of Florida beef to the Confederate cause, Finegan gave cattle baron Jacob Summerlin permission to select thirty men from the state troops under his command to assist in rounding up herds to drive north.[11]

At this time, the principal Confederate military post in east Florida was dubbed "Camp Finegan" to honor the state's highest-ranking officer. It was about seven miles (11 km) west of Jacksonville, south of the rail line near modern Marietta.[12]

In 1863, Finegan complained of the large quantity of rum making its way from the West Indies into Florida. Smugglers were buying it in Cuba for a mere seventeen cents per gallon, only to sell it in the blockaded state for twenty-five dollars per gallon. He urged Governor John Milton to confiscate the "vile article" and destroy it before it could impact army and civilian morals.[13]

In February 1864, General P.G.T. Beauregard began rushing reinforcements to Finegan after Confederate officials became aware of a build-up of Federal troops in the occupied city of Jacksonville. As Florida was a vital supply route and source of beef to the other southern states, they could not allow it to fall completely into Union hands.[14]

On February 20, 1864, Finegan stopped a Federal advance from Jacksonville under General Truman Seymour that was intent upon capturing the state capitol at Tallahassee. Their two armies clashed at the Battle of Olustee, where Finegan's men defeated the Union Army and forced them to flee back beyond the Saint Johns River. Critics have faulted Finegan for failing to exploit his victory by pursuing his retreating enemy, contenting himself by salvaging their arms and ammunition from the battlefield. But, his victory was one rare bright spot in an otherwise gloomy year for the dying Confederacy.[15]

Some Finegan detractors believe he did little more to contribute to the Confederate victory at Olustee than to shuttle troops forward to General Alfred H. Colquitt of Georgia, whom they credit for thwarting the Federal advance. They point out that Finegan was quickly relieved of his command over the state troops, replaced by Major General James Patton Anderson. But this change in command was necessary as Finegan was ordered to lead the Florida Brigade in the Army of Northern Virginia, where he served effectively until near the end of the war.[16]

Col David Lang was the brigade's last commander before the surrender after the Battle of Appomattox Court House.

Postbellum career

[edit]Brigadier General Finegan returned to Fernandina after the war to discover his mansion had been seized by the Freedmen's Bureau for use as an orphanage and school for black children. It took some legal wrangling, but he was eventually able to recover this property. He had to sell most of his lands along Lake Monroe to Henry Sanford for $18,200 to pay his attorneys and other creditors. He did retain a home site at Silver Lake. Adding to his sorrows was the untimely death of his son Rutledge who died April 4, 1871, precipitating a move to Savannah, Georgia. There, Finegan felt at home with the large Irish population and worked as a cotton broker.[6]

It was while living in Savannah that Finegan married his second wife, the widow Lucy C. Alexander, a Tennessee belle. They eventually settled on a large orange grove in Orange County, Florida.[17] Finegan died October 29, 1885, at Rutledge, his orange grove named after his late son in Orange (now Seminole) County, Florida.[18][19] According to the Florida Times Union, his death was the result of "severe cold, inducing chills, to which he succumbed after brief illness." The paper described him as "hearty, unaffected, jovial, clear-headed, and keen-witted." He was buried at the Old City Cemetery in Jacksonville.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b International Genealogical Index at

- ^ Blakey, Arch Frederic, Ann Smith Lainhart, and Winston Bryant Stephens, Jr.,, ed. Rose Cottage Chronicles: Civil War Letters of the Bryant-Stephens Families of North Florida, Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1998. Page 129.

- ^ Klug, Mimi. "Guide to the Mary Martha Reid Papers (1821-1890)". Cocoa, FL: Florida Historical Society Library, 2004.

- ^ Robison, Jim and Mark Andrews. Flashbacks: The Story of Central Florida's Past. Orlando, FL: Orange County Historical Society, 1995. Page 34.

- ^ "Public Meetings," Jacksonville News, June 5, 1852, 1.

- ^ a b c Litrico, Charles. "Joseph Finegan: Fernandina's Confederate General". Archived 2008-07-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 1860 Census, Fernandina, Nassau County, Florida, page 403.

- ^ Blakey et al., page 128.

- ^ Blakey et al., page 129.

- ^ Taylor, Robert A. Rebel Storehouse: Florida in the Confederate Economy. Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 1995. Pages 34-35.

- ^ Akerman, Jr. Joe A. and J. Mark Akerman. Jacob Summerlin: King of the Crackers. Cocoa, FL: Florida Historical Society Press, 2004. Page 53.

- ^ Blakey et al., page 126.

- ^ Taylor, page 40.

- ^ Taylor, pages 146-148.

- ^ Taylor, page 150.

- ^ Blakey et al., page 164.

- ^ 1880 Census, 2nd Division, Orange County, Florida, page 408.

- ^ "Death of Gen. Finnegan". Memphis Avalanche. 5 November 1885 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ McCabe, Dermot (1994). "A Famous Clones General". Clogher Record. 15 (1): 124. doi:10.2307/27699381. JSTOR 27699381.

Sources

[edit]- Akerman, Jr. Joe A. and J. Mark Akerman. Jacob Summerlin: King of the Crackers. Cocoa, FL: Florida Historical Society Press, 2004.

- Blakey, Arch Frederic, Ann Smith Lainhart, and Winston Bryant Stephens, Jr., ed. Rose Cottage Chronicles: Civil War Letters of the Bryant-Stephens Families of North Florida, Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1998.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Klug, Mimi. "Guide to the Mary Martha Reid Papers (1821-1890)". Cocoa, FL: Florida Historical Society Library, 2004.

- Litrico, Charles. "Joseph Finegan: Fernandina's Confederate General".

- Robison, Jim and Mark Andrews. Flashbacks: The Story of Central Florida's Past. Orlando, FL: Orange County Historical Society, 1995.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Taylor, Robert A. Rebel Storehouse: Florida in the Confederate Economy. Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 1995.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

External links

[edit] Media related to Joseph Finegan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Joseph Finegan at Wikimedia Commons- General Finegan at the Battle of Olustee